Hidden Heroines: The Forgotten Suffragettes, Maggie Andrews and Janis Lomas (Robert Hale, 2018)

Posted on 1st August, 2023 in Book Review, Suffragettes, Suffragists

Hidden Heroines: The Forgotten Suffragettes is a collection of short biographies of forty-eight women who were involved in the struggle for the women’s franchise. The book was published in 2018, coinciding with the commemorations of the one hundredth anniversary of the granting of the vote to some British women. In spite of the sub-title, not all the women included in the book were suffragettes. Some were suffragists who campaigned using peaceful, legal methods. However, as the introduction notes, “the term [suffragette] was often used interchangeably with the term commonly used to describe law-abiding campaigners ‘suffragists’.”This is the sense in which the term is used in the title.

Personally, I dislike this usage, as did many suffragists during the campaign who disliked, or even resented, being confused with the militants. My own feeling is that if anything is going to contribute to rendering women “hidden” from history it is surely the use of a term that excludes large numbers of them. This wouldn’t matter so much if I thought that “suffragette” did genuinely incorporate “suffragist”, but more often than not it is the militant narrative that dominates the presentation of the suffrage movement. The 2018 commemorations themselves were a case in point, with their emphasis on the images and stories of the militants – the purple, white and green of the WSPU suffragettes everywhere in evidence. [1]

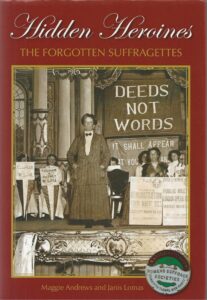

Reassuringly, though, Hidden Heroines delivers on the promise implied in the explanation quoted above and doesn’t focus exclusively on the militants. It’s nice, too, to see some effort to reflect this visually on the front cover, where although images of the militant WSPU dominate (the large front cover photograph and two of the three back cover photographs are of WSPU gatherings) it does also include a badge from the non-militant National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. The women in the book represent a wide range of ideas about women’s suffrage, campaign tactics, and citizenship. Their stories reflect the experiences of women of varied political persuasion, class, income, and social status.

I wasn’t sure, though, that all of the women could be described as “hidden”. Many of them are mentioned in earlier histories such as Antonia Raeburn’s The Militant Suffragettes (1974) or Elizabeth Crawford’s The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2001). Some have entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; some are the subjects of one or more biographies; or they have published autobiographies; others have websites or blogs devoted to them.

I suppose that’s the risk you take when you promise to reveal “hidden” histories or “untold” stories: some smart-alice like me will pounce on the not-particularly-well-hidden. But after all, I’ve been researching, writing and speaking about the women’s suffrage movement for years, so it’s very likely I will have heard of many of the women. Many other readers (perhaps that chimerical beast the “general reader”) will not have heard of them. Clearly, it depends on the knowledge – scant, detailed, or nil – that the reader brings with them.

Which led me to ponder on what a “hidden history” actually is. “Hidden” can’t mean simply “I (the reader) haven’t heard of it”. There are plenty of things I haven’t heard of, or that I’ve heard of but know nothing about – cricket, for example. I couldn’t name more than two or three cricketers, and I certainly couldn’t tell you much about them. That doesn’t mean that every other cricketer is “hidden”. It’s knowledge I could easily find if I wished.

So if something isn’t hidden simply because I haven’t heard of it, then when is it hidden? Is it when lots of other people haven’t heard of it either? But does the fact that a certain number of people haven’t heard of something mean it’s hidden? Obscure, perhaps. A minority interest, possibly. But hidden?

Perhaps it means that the knowledge is not easy to find, or cannot be found at all. As the editors of Hidden Heroines remark, “We have found traces and mentions of numerous other women about whom very little is known or able to be known.” Records about them are simply not there; perhaps they have not survived, or never existed: “many suffrage campaigners remain hidden from history”.

The WSPU office, Clement’s Inn

But is the absence of records the same thing as “hidden”? Doesn’t “hidden” imply that there is a “from whom” and “by whom” – someone from whom something is hidden, and someone by whom it was hidden? This is, of course, exactly what has happened with much of women’s history: it has been concealed, excluded, or ignored by gender-biased histories (throw in race, class, social status, ablist and sexuality biases too) that have focussed on what Jane Austen called “The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page…and hardly any women at all.” [2] But is this exclusion evidence of deliberate or intentional concealment?

Well, yes, in many ways it is. Women’s lives have not been deemed worthy of documentation: they have been confined to private domestic spaces where their activities are (obviously) too trivial to earn a place in history. When they have played public roles, these have often been overlooked or under-reported. Another stumbling block is women’s loss of identity, for example on marriage. It can be difficult to follow the trail of someone whose name has changed. In addition, married women were often known by their husband’s names, as reflected here in the chapter title: “Mrs Arthur Webb (1874-1957) Suffragist domestic goddess”.

Even so, there is plenty of information to be found about many of the women included in Hidden Histories. It is there in the archives and the newspapers if you go looking for it. It is there in the biographies and books, in the public and on-line archives. Even if you don’t have access to the resources of a university, or money to spend on travelling to archives or paying subscriptions for newspaper archives or on-line archives, many public libraries and websites provide access for free to at least some of these resources. In addition, some of the women in Hidden Heroines have left collections of letters and papers, many of which are freely accessible to view by arrangement with the archive.

If you live within striking distance, I’ll be talking about some of the freely-available research resources in “Was your Granny a Suffragette?” at the next Hawkesbury Upton Literature Festival on 30 September 2023. Details and tickets at Eventbrite.

Having the time, energy and inclination are, of course, different matters. Not everyone is able or wants to spend their lives poring over the archives – and the sheer size of some collections means that it really can take up a large part of your life. There are, for example, nine boxes of papers on Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, one of the women included in the book, at Girton College Archives. Unless you’re writing a full-length biography, you’re unlikely to undertake the task of studying them. But does that mean that the information is “hidden”?

Perhaps “hidden” means that information is there but no one has drawn attention to it or made it easily accessible to a wide audience in the form, perhaps, of books like Hidden Heroines. I suppose that’s ultimately the role of the biographer: to follow the scattered clues, gather up the information, arrange it, interpret it, and present it in a readable form. And that’s what the authors of the chapters in Hidden Heroines have done very nicely in this collection of short biographies which illuminate the lives of some fascinating women, hidden or not, all of which I thoroughly enjoyed reading.

- I explored this in an article on Welsh suffragist Winifred Coombe Tennant (‘A fine thing gone wrong’: Winifred Coombe Tennant and the Suffragettes) who urged that the distinction between “suffragette” and “suffragist” should be clarified.

- Northanger Abbey, Jane Austen.

Picture Credits

WSPU Office, Clement’s Inn, 1911 – Women’s Library on Flickr, no known copyright restrictions.