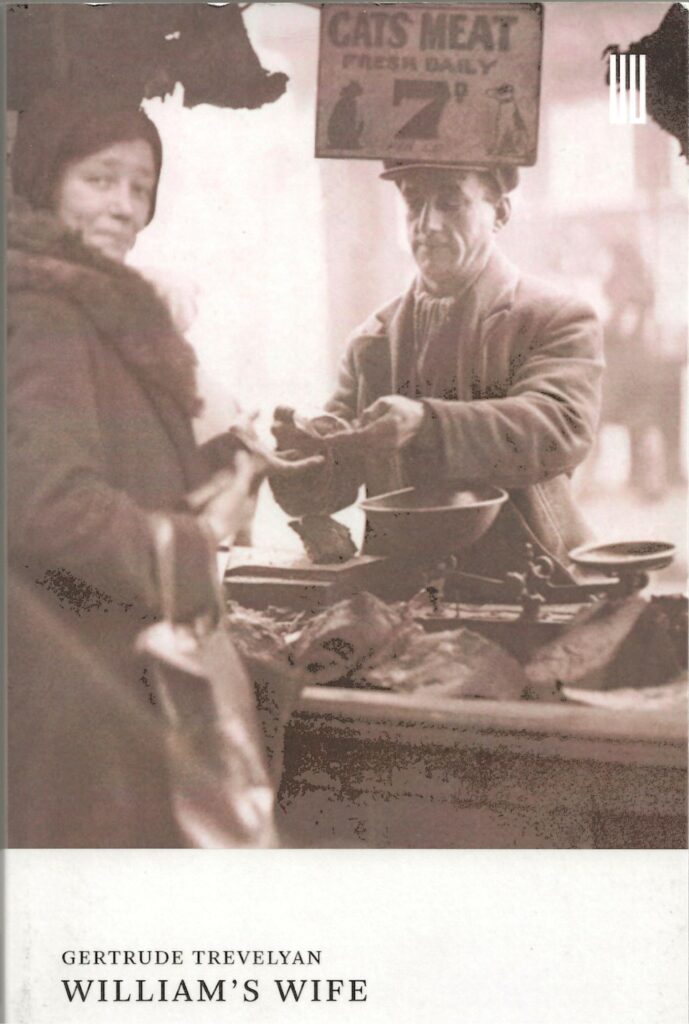

William’s Wife, Gertrude Trevelyan, Boiler House Press, 2023 (first published 1938)

Posted on 2nd November, 2024 in Book Review

William’s Wife is an unpleasant novel about unpleasant people. It draws you in to an ugly world of dark and neglected rooms; hideous, bulky old furniture; and musty, outworn clothes, green with age. It draws you into an oppressive, claustrophobic milieu, with its small cast of characters – much of the human interaction is between Jane and William alone – and even their small circle shrinks over time. Above all, it draws you in to the workings of a mind which is not a particularly nice one. Jane Chirp, the wife of the title, is narrow, mean and suspicious, and it is these traits which develop at the expense of any kinder or more generous impulses she might have possessed.

All this is repulsive, but it is also compelling. This is achieved in large part through the impressive handling of point of view, which never veers from that of Jane. On the contrary, the focus on her becomes ever sharper, until eventually, the prose develops into a disjointed stream of consciousness: “Handbag and shopping and black and that one…Oh, oh dear, what a turn. Take no notice, that was the only thing. Take no notice and he’d take himself off. Go the same way he came”.

It might be possible to read the story of Jane’s ill-judged marriage to William Chirp from a feminist perspective. Here we have a powerless, deprived and increasingly isolated wife dominated by a controlling, coercive, miserly husband who has the knack possessed by all such characters of killing hope and joy stone dead. But it isn’t quite as simple as that. Selfish and narrow-minded he might be, but Jane meets him at least half-way in those qualities.

From the outset she is revealed as someone who is obsessed with money, with saving and getting value from things and people. She married William for money and status and in her new station she is a horrible snob, affecting a “haughty air” when she goes shopping, expecting the shop keeper to be “very respectful, as was fitting” . She has a mean and narrow mind which makes her suspect everyone around her of wanting to cheat her. She thinks that William’s daughter only visits because she wants something, servant girls are all lazy and have to be watched like hawks or they’ll skimp on their work, their food must be carefully doled out to them. Respectability is everything: walking “in a proper manner, to church”, looking “ladylike”, fearful of being caught looking out of the window.

Even so, her position is an unenviable one. William refuses to let her have access to the money she had saved before she married. He times how long she takes when she goes out shopping. He’s too mean to do repairs in the house or give her money for new clothes. They bring out the worse in one another, and as she resorts to ever meaner and more sordid subterfuges for getting money out of her mean and sordid husband, she becomes mean and sordid herself. Her descent to mind-wrecked bag lady picking up scraps of food in the street is horrible.

But who was Gertrude Trevelyan, that she could depict these mad and squalid lives with such convincing clarity?

Gertrude Evelyn Trevelyan was born in 1903. She studied history at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, where she became famous in 1927 as the first woman to win the Newdigate Prize for poetry. She started a trend: the prize was again won by women in 1928 and 1929.

Her poem, ‘Julia, Daughter of Claudius’, was inspired by the story of the discovery in Rome in 1485 of the marble tomb of a fifteen year old girl, described as “Julia, Daughter of Claudius”. The beautiful girl’s body was said to be uncorrupted (“Awake! For Julia lives. Awake! / For beauty is not dead” enthuses Trevelyan), and people flocked to see her. Fearing that a cult might develop around the pagan girl (uncorrupted bodies being the prerogative of saints), the Pope had Julia’s body removed at night and secretly re-interred.

News of Trevelyan’s success was widely reported in the press. She was feted at a lunch at the Lyceum Club, where suffragist and co-founder of the Townswomen’s Guilds Margery Corbett Ashby took the chair, and Trevelyan read her poem in a “clear, girlish voice” to a “spellbound” audience (The Vote, 15 July 1927). Mary Plowman read the poem on BBC Radio, and it was published by Basil Blackwell. Trevelyan later said, “I did it for a joke.” (Birmingham Gazette, 9 June 1927). (NB is Mary Plowman another forgotten woman? Apart from a reference to a one-act radio play she wrote, I can’t find any information about her.)

After leaving Oxford, Trevelyan lived in Notting Hill, London on an allowance of £500 a year from her father. By 1940 she had published eight novels. Her books certainly seem original. Her debut (Appius and Virginia) is about a woman who raises an orangutan as if it’s a human child. Critics seem to have been divided between those who praised it for its boldness and daring, and those who thought it was silly. As It Was in the Beginning is a stream of consciousness novel about a dying woman, and Trance by Appointment is about a psychic.

Gertrude Trevelyan died, aged thirty seven, at her parents’ home in Bath as a result of injuries suffered during an air raid on London in 1941.

Regarded as an “experimental” novelist, Trevelyan’s works may be enjoying something of a revival. Boiler House Press have brought out two further novels, Two Thousand Million Man-Power and As It Was in the Beginning.