Captain James Cook at the British Library – Exhibition

Posted on 20th August, 2018 in Captain Cook, Great Southern Continent

In August 2018 I saw the British Library exhibition “Captain Cook: The Voyages”. I was particularly interested in it because Cook’s voyages were one of the inspirations behind my first historical novel, To The Fair Land.

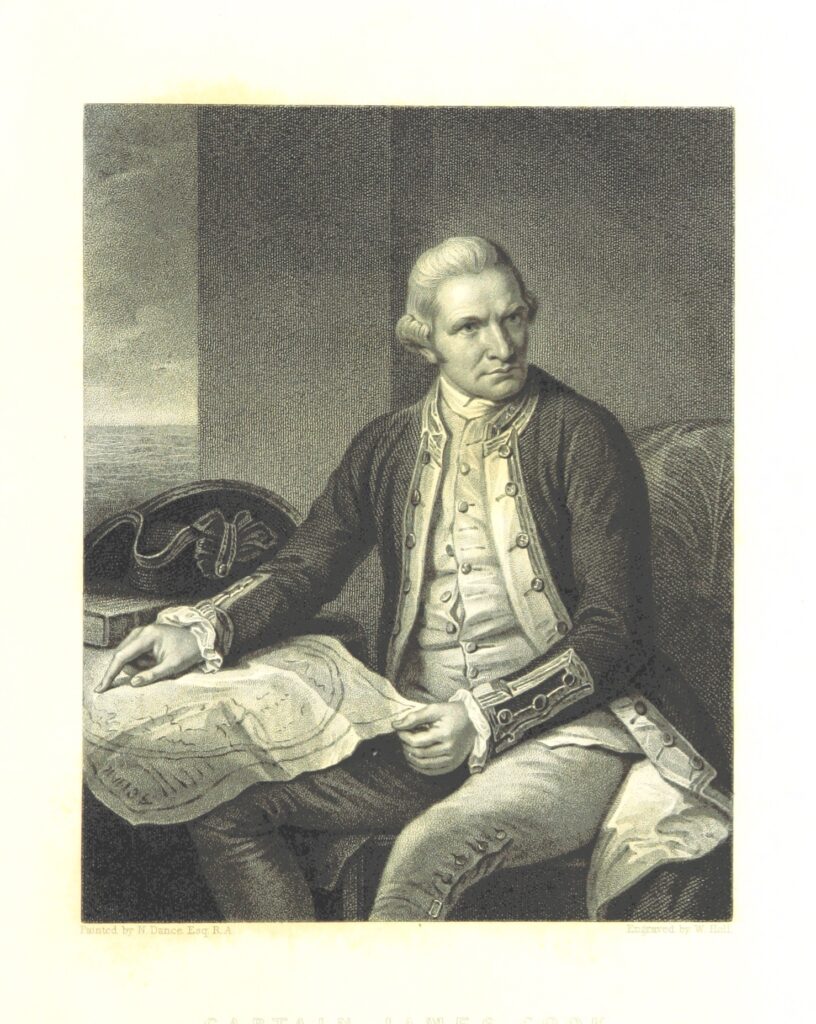

It was 250 years since Captain Cook set sail from Plymouth on HMS Endeavour on 26 August 1768. The voyage lasted until 1771, and was followed by two further expeditions from 1772 to 1775 and 1776 to 1780. Cook was killed in a skirmish on Hawaii on 14 February 1779.

The voyages were motivated by a combination of scientific curiosity and expansionism. The goal of the first voyage was to observe the Transit of Venus at Tahiti, though it also had another, secret motive. This was the search for the Great Southern Continent, a land mass which was believed to exist in the southern hemisphere. By the end of the second voyage, Cook had proved that the continent did not exist. Though that was disappointing for a Britain looking to extend its empire, there were plenty of other lands for the British to seize and that is what Cook, acting under orders, did. As the exhibition pointed out, the fact that those lands were already inhabited was no barrier to claiming them for George III.

Maori trading a crayfish.

The exhibition did a good job of bringing home the impact of those strange meetings on distant shores, when two cultures collided, often with fatal results. It offered different perspectives, looking at the expeditions from the point of view of the explorers and those you might call the explored. This is most effective when we heard voices from the descendants of those who encountered Cook. It also touched on how Cook and his voyages have been mythologised, for example in a fascinating exploration of the different depictions of Cook’s death which waver between showing him as a man of peace and an invader.

Captain Cook

I would like to have seen more about the ideology behind the science of the voyages, which to me seems connected with the imperial project. It was a science that sought to classify, control and utilise. It was a destructive science in the days when collecting specimens meant removing them from their habitats. It was a cruel science willing to inflict pain on the animals it studied, which were killed before being drawn and preserved. It was a science in the service of the state, industry and commerce. It would be valuable to explore how, if at all, any of this has changed.

I doubt that the debates about the scientific and imperial aspects of Cook’s voyage will ever be resolved. Was Cook a hero, or an imperialist invader? A scientist, or a plunderer? This nicely balanced exhibition will give you much to think about on these and other aspects of the voyages. It also includes some wonderful artefacts, amongst them drawings, logs and journals, including Captain Cook’s own. There was also a fascinating book to accompany the exhibition – James Cook: The Voyages – which I couldn’t resist buying.