Commemorating eighteenth-century women writers and artists in Clifton, Bristol

Posted on 5th July, 2024 in Bristol, Eighteenth Century

Clifton in Bristol has many literary connections, not least of which is that it is the setting for much of Frances Burney’s first novel, Evelina (1778). Jane Austen visited in 1806, and Clifton features in her novels Emma, Persuasion and Northanger Abbey. Novelist Maria Edgeworth (1768–1849) also visited Clifton. Her brother-in-law, Dr Thomas Beddoes (1760–1808), who lived in Rodney Place, established his Pneumatic Institute in Dowry Square, Hotwells. Here he treated many of the ailing people who came to Bristol to take the waters at the Hotwells spa. Beddoes treated tubercular patients using nitrous oxide (laughing gas). Edgeworth was one of the many literary visitors who tried the gas for recreational purposes; others included Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834) and Robert Southey (1774-1843).

Other eighteenth-century women writers and artists who had connections with Clifton have been commemorated by plaques placed by the Clifton and Hotwells Improvement Society.

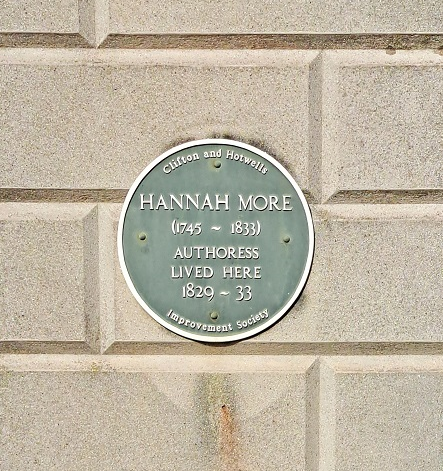

Hannah More, 4 Windsor Terrace

Hannah More (1745-1833) was born in Fishponds, Bristol. Her father was a schoolteacher, and his daughter enjoyed a wider education than that usually allowed to girls. The family moved to Bristol where her father set up schools for boys and girls. The girls’ school was later situated on Park Street, and Hannah ran it with her sisters, Mary, Elizabeth, Sarah and Martha.

Hannah was for a time engaged to wealthy Wiliam Turner, who later jilted her. To compensate her, he settled an annuity on her which gave her financial security and independence.

She was a playwright and essayist, whose work had a moralistic, evangelical and conservative outlook. She was was on the committee of the Female Anti-Slavery Society in Bristol, and a friend of William Wilberforce’s. In 1788 she wrote the anti-slavery poem, Slavery. She set up charity schools for poor children where they were taught to defer to their social betters. She lectured the poor on their duties in a series of tracts, warning them particularly against the dangerous ideas of the French Revolution. Her best-selling 1799 book on women’s education, Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education, rejected Mary Wollstonecraft’s demand for women’s rights.

In 1784 she moved to Cowslip in Somerset. By 1801 her sisters had retired from teaching, and she moved with them into a house in Wrington, Somerset. By 1819 all of her sisters were dead. In 1828 she moved to Clifton in Bristol, where she died in 1833. She was buried at All Saints’ Church in Wrington with her sisters.

Hannah More’s relationship with Ann Yearsley (see below) was one of the inspirations for my novel, Death Makes No Distinction: A Dan Foster Mystery.

Windsor Terrace, Clifton, Bristol

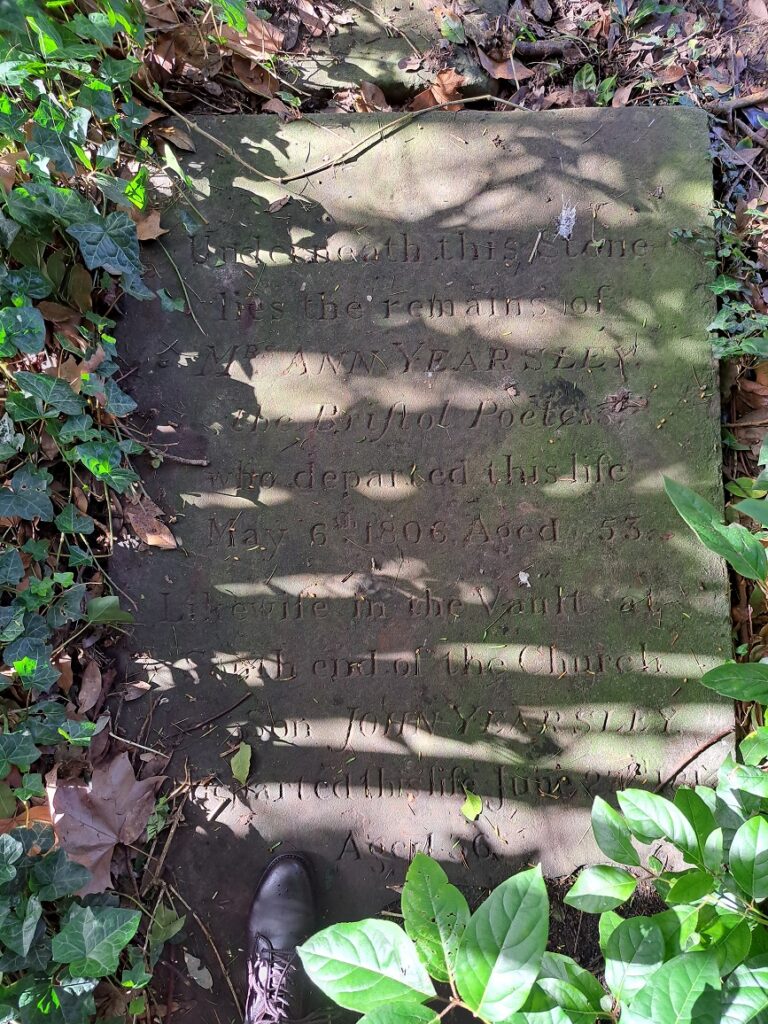

Ann Yearsley, St Andrew’s Churchyard

Poet Ann Yearsley, née Cromartie, (c1753–1806) was born in Bristol. Her mother was a milkwoman, and it was she and Ann’s eldest brother who taught Ann to read and write. Nothing is known about her father.

Ann was brought up to take over her mother’s trade, which is how she earned the title “Lactilla” when she became a published poet. She was married to labourer John Yearsley, and they had six children. The family was poor, and at times relied on philanthropy to survive. In spite of her disadvantages, Ann wrote poetry. The cook at the More sisters’ Park Street school showed some of Ann’s work to Hannah More, who was so impressed that she took on the role of patron.

Ann Yearsley’s grave in the medieval churchyard of St Andrew’s Church

More taught Ann grammar and spelling, and arranged for Yearsley’s first collection, Poems, on Several Occasions, to be published by subscription in 1785. However, the arrangement broke down over disagreements about the management of Ann’s earnings, which More took upon herself. Ann, however, demanded access to the funds. At the same time, More thought that Ann was overstepping the boundaries of her station in life, and the relationship broke down.

Ann found a new patron, Frederick Augustus Hervey, the Earl of Bristol. She used some of her money to set up a circulating library in Hotwells, Bristol. She published more poems, a play and a historical novel. After the death of her husband in 1803, she moved to Melksham, where she died in 1806.

Ann Yearsley’s grave is hidden away in a leafy corner of the graveyard at St Andrew’s church. The church itself is long gone, a victim of the Blitz, and was demolished in the 1950s.

Hesther Thrale, 10 Sion Row

Hester Thrale (1741–1821) is described on her CHIS plaque as “Dr Johnson’s friend”. In fact, she was a great deal more than that. She was a writer, poet, traveller, biographer and diarist (Thraliana: The Diary of Mrs Hester Lynch Thrale Piozzi 1776-1809).

She was born at Bodfel Hall, Pwllheli, Wales. Her family was well-connected, but not wealthy. After her mother’s death her father remarried, and after his death Hester herself was married, for money not love, to the rich brewer Henry Thrale (1728-1781). It was not a happy marriage. She had twelve children, only four of whom survived to adulthood; he had numerous mistresses.

The Thrales lived on his 109-acre estate in Streatham where she presided over a literary salon which included Dr Johnson, who lived at Streatham Park from 1766; Frances Burney; Oliver Goldsmith; and Elizabeth Montagu. The house was demolished in 1863 and the estate built over with housing.

In 1772 Hester Thrale took over running the brewery which her husband’s mismanagement had brought close to ruin. After her husband’s death she sold the brewery and moved to Harley Street. In 1784 she married Gabriel Mario Piozzi (1740–1809), an Italian musician. Many of her friends were appalled by the match, and she was criticised for ‘deserting’ Dr Johnson and her children. Her eldest daughter, Hester (known as Queeny), was bitterly opposed to the marriage. Frances Burney thought the match unwise, and said so, but remained friends with Hester Thrale until after the Piozzis’ marriage, when her congratulations were thought too lukewarm by Mrs Piozzi and the two were estranged. Frances Burney thought the breach was initiated by Mr Piozzi. Years later, however (in 1818), the women’s friendship was resumed.

The Piozzis lived at Streatham Park from 1790 to 1795, when they moved to Wales. Here Mrs Piozzi had a house, Brynbella, built near Tremeirchion. She continued to write, and also translated some of Hannah More’s improving tracts for the poor into Welsh. The couple adopted her husband’s nephew, John Salusbury Piozzi, in 1798.

Piozzi died in 1809. Mrs Piozzi made John Salusbury Piozzi her heir and gave him Brynbella in 1814, when she moved to Bath. In 1820 she took a house in Royal York Crescent in Clifton. After a visit to Penzance, she moved into lodgings on Sion Hill, Clifton while some repairs were carried out at the house in Royal York Crescent. Here, after a fall in March 1821 sustained on the journey back from Penzance, she died in in May 1821. She was buried next to Piozzi at Tremeirchion.

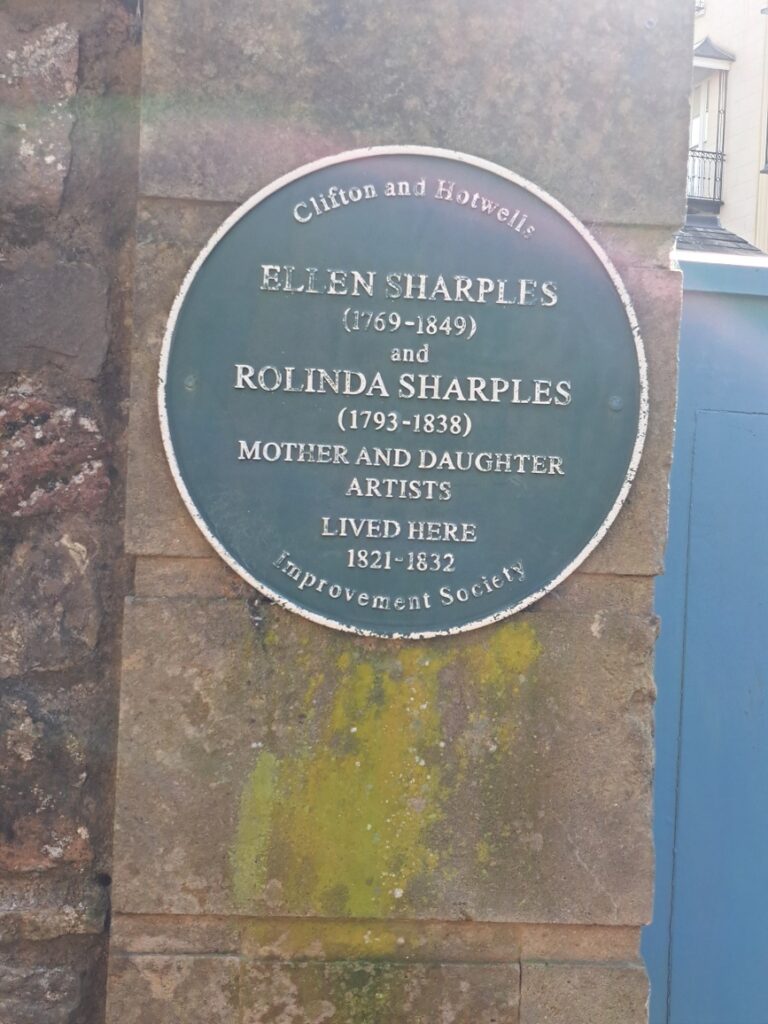

Ellen Sharples and Rolinda Sharples, 37 Canynge Road

The Sharples were a family of Bristol artists. Ellen Sharples (1769-1849), her husband James Sharples (1751/2-1811), their daughter Rolinda Sharples (1793/4-1838), Rolinda’s half-brother Felix Sharples (c1786-1832), and her brother James (c1788-1839) were all genre and portrait painters. Ellen had been James Sharples’s pupil before their marriage.

The family lived in America between 1793 and 1801 and from 1806 to 1811, returning to Bristol after the death of James Sharples senior in New York in 1811.

Rolinda Sharples painted many scenes of Clifton and Bristol life and society, including the Clifton Assembly Rooms, St James’s Fair, and Clifton Race Course. Many of her paintings are now in Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.

Mother and daughter lived in Canynge Road between 1821 and 1832. They then lived in 3 St Vincent Parade, Hotwells, where Rolinda died of breast cancer in 1838. She was buried in St Andrew’s churchyard.

Ellen Sharples was a founder of the Royal West of England Academy. She donated £2,000 to the Academy, and on her death bequeathed money and her family’s paintings to it.

You can see some of Rolinda Sharples’s paintings at Art UK and also read an article by Thangam Debbonaire, ‘Rolinda Sharples and the Bristol School of artists’.

St Andrew’s Churchyard, Clifton, Bristol