Gertrude Baillie-Weaver: anti-vivisectionist, suffrage campaigner, theosophist

Posted on 10th August, 2025 in Gertrude Baillie-Weaver, Suffrage Spotlight, Women Writers' Suffrage League

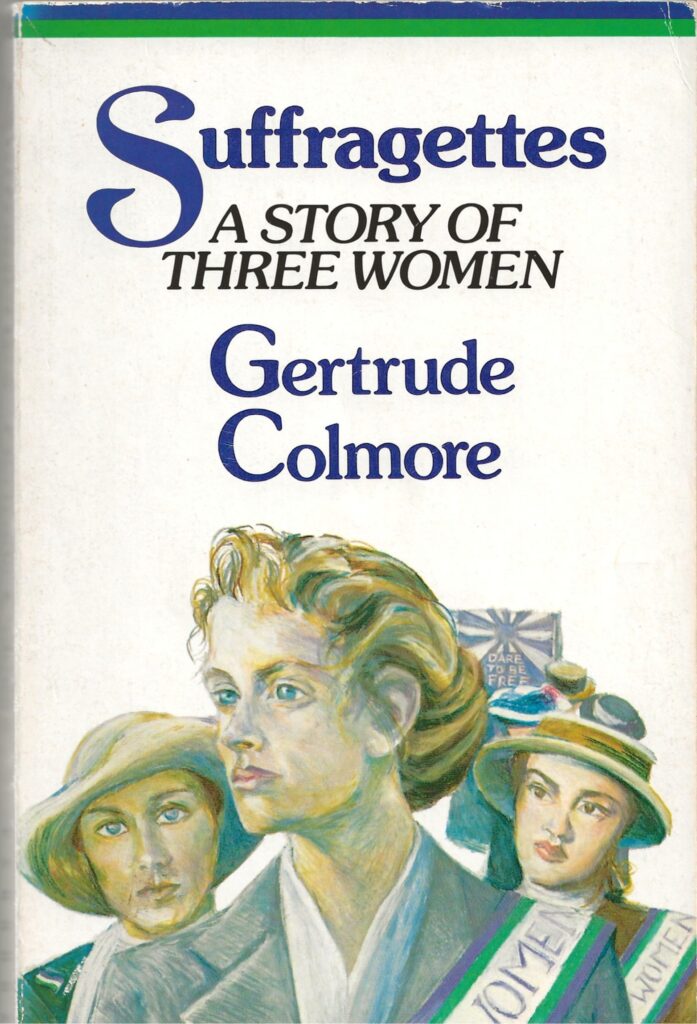

If she is remembered at all Gertrude Baillie-Weaver is best known as the author G Colmore (George or Gertrude Colmore) whose 1911 novel Suffragette Sally was republished by Pandora Press as Suffragettes: A Story of Three Women in 1984. In fact, she was a prolific novelist, poet, and short story writer, and suffrage was not the only cause she wrote about. Arguably, she should be remembered at least as as much for her work for animal rights as for women’s right to vote.

The 1984 Pandora reprint, entitled Suffragettes: A Story of Three Women.

Gertrude Renton was born in 1855 in Kensington, London into a Quaker family. Her father was a stockbroker. She married her first husband, barrister Henry Arthur Colmore Dunn, in 1882. After his death in 1896, she married Harold Baillie-Weaver (1860-1926), who was also a barrister and came from a Quaker family, in 1901. After their marriage the Baillie-Weavers lived in Newport, Essex. In 1920 they moved to Wimbledon, Surrey.

The Baillie-Weavers shared a commitment to many progressive causes. They both supported the suffrage campaign. Gertrude was a member of the Women’s Freedom League (WFL), and the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Harold was a member of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, and frequently spoke at suffrage meetings organised by the WSPU and the WFL.

Gertrude does not seem to have done as much speaking as her husband, perhaps preferring to make her contribution through her writing. She donated books to the WSPU for fund raising sales, and also wrote a number of short stories, poems and articles for The Vote, the journal of the Women’s Freedom League. The publication of her story Unnecessary (The Vote, 14 March 1913) about young girls who were pregnant or suffering from venereal disease prompted a further investigation in The Vote (27 June 1913) which quoted statistics about child abuse provided by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. The sexual abuse of children and women was one of the reasons women demanded the vote. With it they hoped to reform the all-male legal system which excluded women from the court room during the hearing of rape and assault cases, and often handed down light sentences.

Many of Gertrude’s stories for The Vote were included in the anthology Mr Jones and the Governess published by the WFL in 1913. In 1913 she wrote The Life of Emily Wilding Davison, which was republished in Ann Morley and Liz Stanley’s The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison (London: The Women’s Press, 1988).

Banner with WFL motto

She was a member of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League (WWSL), and walked in the WWSL’s contingent in the June 1911 Coronation Procession. In July 1914 the Baillie-Weavers attended a costume dinner and pageant held by the Actresses’ Franchise League and the WWSL. She went as the Scottish writer Joanna Baillie (1762-1851), and he as Joanna Bailey’s friend, though many guests mistook him for Walter Scott.

The Theosophical Society’s League to Help the Woman’s Movement was founded in 1913/4. Harold Baillie-Weaver was chairman, and Gertude was on the executive council. The League took a neutral stance on suffrage tactics and met for meditation and discussions on women’s suffrage. In 1914 the Baillie-Weavers were founding members of the United Suffragists, with the Pethick-Lawrences and Evelyn Sharp, and were both vice presidents.

During the First World War the Baillie-Weavers were pacifists. Gertrude was a member of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. She wrote pacifist-themed short stories for The Vote. Aliens (The Vote, 23 July 1915) is set during anti-German riots. Amelia (The Vote, 21 April 1916) pokes fun at the anti-suffragists who before the war went to meetings “to tell each other that they ought to stay at home”, but who changed their tune during the war and urged women to work outside the home.

Harold chaired the Peace Council, which campaigned for a negotiated peace. Conscientious objector Bernard N Langdon Davies, who consulted Harold about whether or not he should go to prison, described him as a “man of exquisite mental and sartorial culture and also of something very near to saintliness”. (Quoted in ‘Alternative Service’, B N Langdon Davies, in We Did Not Fight 1914-18 Experiences of War Resisters Ed Julian Bell, London 1934, p. 192.)

The Baillie-Weavers worked unceasingly for animal rights. They were members of the National Canine Defence League (NCDL); Gertrude was secretary of the local branches of the NCDL and Our Dumb Friends’ League. Harold was a member of the Humanitarian League. In the 1920s Gertrude chaired the National Council for Animals’ Welfare Week. They were both vegetarians and promoted clothing without the use of “fur, feathers or leather” (Woman Teacher, 23 April 1926). They were anti-vivisectionists, and much of Gertrude’s work deals with vivisection and the treatment of animals. The Angel and the Outcast (1907) exposed conditions in slaughter houses.

Gertrude wrote to Zola and asked him to write an anti-vivisection novel. Zola did not reply, and died shortly after. Gertrude realised then “that I, to the best of my ability, must carry out the task, and shrinking and dreading it, I began preparations for doing so” (The Bystander, 17 February 1909). The result was Priests of Progress (1908) (published as G Colmore), which tells the story of a woman married to a physician. When she witnesses her husband operate on a dog, she is converted to the opposition to vivisection.

Many reviewers assumed the author of Priests of Progress was a man. Others called for the assertions she made to be repudiated, and described them as exaggerated. She responded with a letter to the press pointing out that the incidents she described in the novel were based on fact and that she had given “chapter and verse in an appendix” which cited sources (G Colmore, Manchester Courier, 8 January 1909). By contrast, some welcomed the book as it would open up discussion. Some criticised the use of a novel for ‘propaganda’ purposes at all.

The Baillie-Weavers were both theosophists. Harold was general secretary of the Theosophical Society from 1916 to 1921, and a member of the Esoteric Section, the Order of the Star in the East and the Universal Order of Co-Freemasonry. He chaired the Theosophical Educational Trust, which ran the Theosophical School (later St Christopher’s, also known as Arundel School) in Letchworth, which was opened in 1915.

Harold Baillie-Weaver died at their Wimbledon home on 18 March 1926. Gertrude Baillie-Weaver died later that year, on 26 November, after an illness. Her final novel (A Brother of the Shadow) was published a month before she died. She left bequests to the National Canine Defence League, the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals, the Council of Justice for Animals, the Anti-Vivisection Society, the Performing Animals’ Defence Society, and the Theosophical Society. She was remembered in The Vote as “a very early member of the Women’s Freedom League, and always exceedingly kind and helpful in every way…With a very pleasing, magnetic, gentle personality and high courage” (The Vote, 10 December 1926).

The National Council for Animal Welfare commissioned a statue to commemorate the Baillie-Weavers’ work for animals. The statue, the Goatherd’s Daughter, also known as The Shepherdess, is by Charles Hartwell (1873-1951) and was unveiled in Regent’s Park in 1932. It now stands in St John’s Lodge Gardens, Regent’s Park.

Picture Credits

Women’s Freedom League banner: Women’s Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions