How a terrier called Peg helped women get the vote

Posted on 6th July, 2025 in Suffragette Dog Licence Protest, Women's Tax Resistance League

Today suffragette militancy is often equated with the Women’s Social and Political Union’s (WSPU) policy of attacking property by, for example, smashing windows or burning down buildings. However, there were suffrage campaigners who were militant but non-violent, and whose law-breaking took less destructive forms. One of these forms was refusal to pay taxes, citing the argument “no taxation without representation”.

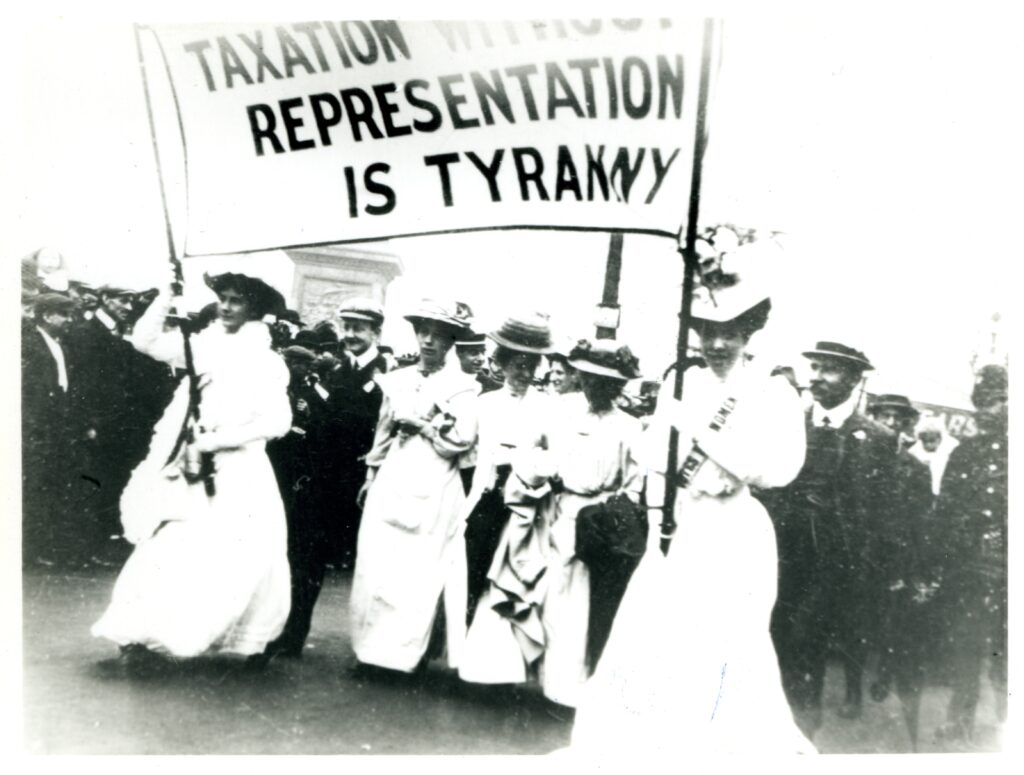

Women’s Tax Resistance League procession

The Tax Resistance League (TRL) was formed in October 1909. It had close connections with the Women’s Freedom League (WFL), which had been established in 1907 as the result of a split in the WSPU. However, tax resistance was not limited to WFL members. Many WSPU suffragettes, as well as members of other suffrage organisations, used tax resistance as a means of protest. The secretary of the WFL, Mrs Kineton-Parkes, saw tax resistance as a tactic that could appeal to women who approved of militancy but were unable to engage in it. She also thought it could unite militant and non-militant campaigners.

At first glance, it seems obvious that the policy could appeal only to well-off women who owned property or who earned a taxable income – professional women such as actresses, doctors or university lecturers. Other taxes such women might be liable for included carriage licences, Armorial Bearings (the display of coats of arms), and Liveried Servants. There was, though, one tax which women on lower incomes could be liable for, and that was the dog licence.

The dog licence was renewable annually on 31 December using forms available from Post Offices, and since it amounted to only a few shillings (7s 6d), it might seem that the penalties for non payment were negligible. In fact, they could include imprisonment and distraint of goods. So what sort of women refused to pay their dog licences, what happened to them, and what happened to their dogs?

The women who refused to pay their dog licences came from a variety of backgrounds. I’ve picked out a selection of protesters from the many cases I came across.

Margaret Rodgers, a laundry proprietress of Willesden. In November 1912 she was fined 7s 6d. She was applauded in court when she declared she would never take out a dog licence while women did not have the vote, and nor would she pay the fine. In December some of her belongings were sold. Mrs Kineton Parkes made a speech in the auction room, and afterwards a meeting was held on Kilburn High Road. In July 1913 Mrs Rodgers’s goods were again seized for non-payment of taxes. The WFL held a protest meeting on Willesden Green. Apart from suffrage, Mrs Rodgers was interested in social work, and proposed a residential scheme for working women.

Alice Walters (1871-?), a music teacher, was a WSPU organiser in Bristol, window breaker, and TRL member. She was summoned in March 1913 and spent seven days in Horfield Goal (now HMP Bristol). She was summoned again in April and refused to appear in court. She was fined again and spent another seven days in prison. She received a third sentence of a week in prison, and in August faced her fourth spell in prison; I don’t know if she served this sentence. While she awaited the outcome of this summons, she and her dog “are enjoying a good holiday” reported The Vote (1 August 1913).

Her dog’s name was Daniel but she decided to rename him Peg, explaining it was “because I use him to hang my protest on” (The Vote, 1 August 1913).

Hortense Lane of Ipswich (?-1937) was brought up in a wealthy family, but was cut off by her widowed mother after she married stable groom Frank Lane. She and Frank lived on and ran Cowslip Farm, which was was owned by Dr Elizabeth Knight, who lived in London. When she died in 1933, Dr Knight left the farm to Hortense.

Hortense appeared at Woodbridge Police Court in 1911 charged with refusing to pay her carriage and dog licences. She had seven dogs on the farm; four had licences but three did not. She said the untaxed dogs belonged to her and her fellow suffragettes Constance Andrews, WSPU organiser in Ipswich; and Dr Elizabeth Knight, WFL treasurer. A number of suffragettes attended court to support Hortense Lane, who was fined. She refused to pay it. After her hearing the suffragettes held a protest meeting outside the court. Hortense Lane and Elizabeth Knight had goods distrained, and a farm hay wagon was sold.

As Constance had “given all her worldly goods to her sister” (The Vote, 10 June 1911) and so had no belongings to cover her fine, she served her prison sentence.

WTRL Procession, 1911

In May 1914 Hortense Lane was at Woodbridge Police Court for again refusing to pay her dog licence. There were then seven dogs on the farm, two of which did not have licences. She said these belonged to herself and and Dr Knight, and she did not see why she should be summoned for someone else’s dog. The bench heard inconclusive evidence about the ownership of the second dog, but in the end Mrs Lane was fined 30s and 15s costs. Members of the WFL held a protest meeting outside the court, at the end of which they had to be escorted to the police station to protect them from the unruly crowd.

Dr Elizabeth Knight (1869-1933) was a wealthy Quaker who had studied classics at Newnham College, and then trained at the London Medical School of Medicine for Women. She was honorary treasurer of the Women’s Freedom League .

Dr Knight appeared at Hampstead Petty Sessions in October 1912 for non-payment of her dog licence. She refused to pay her fine and was sentenced to seven days in prison. She also withheld taxes in respect of a country residence. She was sentenced again in April 1913 and June 1913.

In all Dr Knight was convicted eight times for refusing to pay her dog licence. “Dr Knight’s famous hay wagon” was distrained and sold on three separate occasions to cover fines. However, on the third occasion the sale was deemed ineffective because the rate collector had reserved the wagon for non-payment of rates.

Dorothy Evans (1889-1944) taught PE at Batley Girls’ Grammar School, but left in 1909 after she was arrested for breaking windows at the Batley Conservative Club. In court she apologised for this action, saying the women’s quarrel was not with the Conservatives, but the Liberal Government. Her father paid her fine against her will and she was released. She went on to be WSPU organiser in Birmingham, organiser in Bristol in 1913, and a suffragette arsonist.

She was sentenced to seven days in prison when she refused to pay her fine for not obtaining a dog licence in 1911. However, she was allowed to go free, prompting Brimingham WSPU organiser Gladys Hazel to conclude that the authorities had decided Dorothy’s protest was a “legitimate…conscientious objection” and hoping that “all women who have hitherto paid their taxes will take full advantage of…their right to resist and will become conscientious objectors” Votes for Women, 21 April 1911).

Events proved Gladys’s optimistic interpretation wrong, and a month later Dorothy Evans was arrested and taken to Winson Green Prison. Gladys Hazel pointed out that this was the first prison to inflict forcible feeding on suffragette prisoners who demanded political prisoner status. However, Dorothy was being treated as a political prisoner and was allowed to have her own food, clothes and books.

Princess Sophia A Duleep Singh, (1876-1948)’s father was the Maharajah Duleep Singh who had been pensioned off by the British government when they annexed the Punjab. He became a naturalised British citizen. Princess Sophia lived in Faraday House at Hampton Court. She was a member of the WSPU and the TRL.

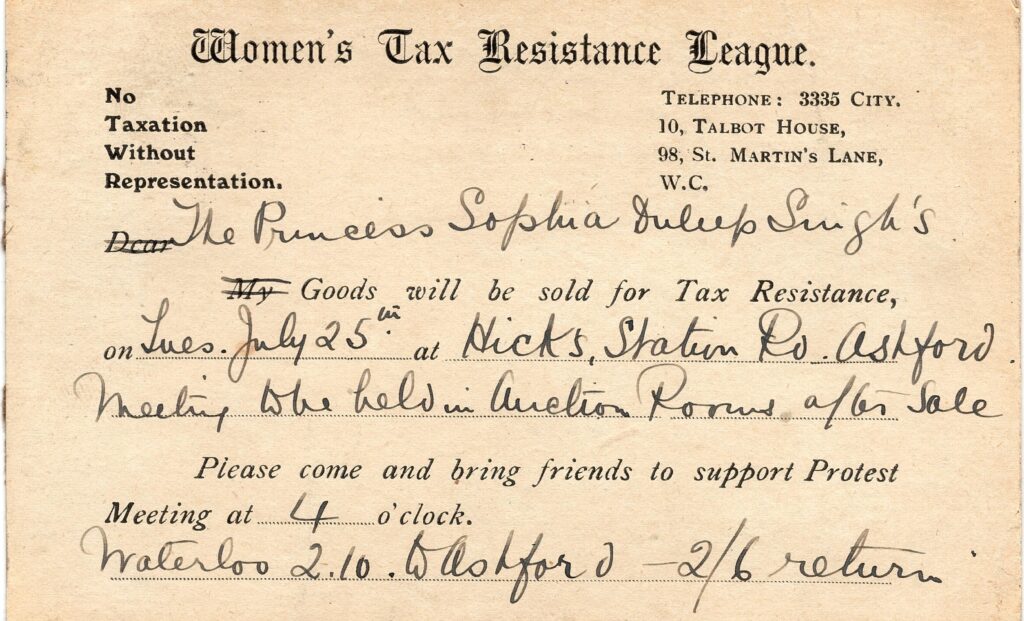

The WTRL invite supporters to the sale of Princess Sophia Duleep Singh’s goods

On 22 May 1911 she was fined at Feltham Police Court for keeping five dogs without licences. She was also summonsed for using armorial bearings, and keeping a carriage and man servant without licences. She admitted all the charges except the one connected with armorial bearings. She did not attend the court and was represented by a solicitor. He had been instructed to protest on her behalf against “the gross injustice of making women liable to taxation who had no voice in the management of the country” (Daily News (London), 23 May 1911). She was fined £1 each on the dog licence, carriage and male servant charges, and the court agreed to give the armorial bearings charge further consideration; subsequently, the charge was dismissed.

In 1911 she also had jewellery distrained for refusing to pay rates.

In December 1913 the Princess refused to pay dog licences for eight dogs, and items of jewellery were distrained to settle her debt.

Isabel Tippet (1880-1969), novelist, WFL member, and author of the suffrage play Such Stuff as ’Eroes Are Made Of, was charged with keeping a dog without a licence in November 1912. Her case was heard on 1 December. She drove to court in a motor car carrying a banner declaring that “Taxation Without Representation is Tyranny”. The car was also covered in bills, one of which read “Who makes the laws. I said the man: that’s my little plan. I make the laws”.

A number of supporters watched Mrs Tippett tell the Bench that she had notified the police in March or April that she did not have a dog licence. It was, she said, scandalous, that it had taken them so long to take her to court. She said that the case was “perfectly ridiculous” and it was “absolutely impossible to attempt to make her pay any fine in so much as, by the law of the country a woman was no longer a person”. The Clerk of the Court decided that it was possible for women to be a person under one Act, but not under another, and the court was “satisfied that Mrs Tippett was a person” (Stowmarket Weekly Post, 5 December 1912). A protest meeting was held in the market place afterwards.

I have found no information on any further action taken against Mrs Tippett.

Emma Sproson (1867-1936) of Wolverhampton, joined the WSPU, but in 1907 moved to the WFL and became a member of the WFL national executive until her resignation in 1912. She was also a member of the WTL and the Independent Labour Party.

She was sentenced to a total of five weeks in Stafford Gaol on charges of not paying her dog licence and also not keeping a ferocious dog under control at hearings on 23 May and 20 June (one week for the dog licence and four weeks for the ferocious dog). She was refused the right to appeal. The WFL and TRL, arguing that the evidence did not substantiate the second charge, demonstrated against these sentences in Hyde Park on 23 July 1911, and there were also demonstrations in Wolverhampton on 26 July. More meetings were planned in Wolverhampton for Emma Sproson’s release in July.

The WFL wrote to Winston Churchill, then Home Secretary. He did not answer their letter and so they arranged for H G Chancellor, MP to raise a question in the House of Commons about the legality of two trials and two sentences for one offence. Churchill replied that Mrs Sproson had in fact been sentenced on two separate charges, and added that the dog had bitten three children. The dog was shot.

Emma Sproson’s husband was also sentenced to seven days in prison for aiding and abetting her. He too was denied leave to appeal.

There were many other women who resisted the dog licence tax, but I think even this small selection shows that these tax resisters came from a range of backgrounds. They were farmers and doctors, laundresses and princesses, teachers and novelists. Some women, like Dr Knight, were serial offenders and appeared in court more than once.

The dog licence protest was something that less wealthy women could take part in. Emma Sproson, speaking at a WFL meeting in May 1911, said that “although [she was] a tax-resister…she was not of the aristocratic classes”. She also pointed out that some taxes, such as those on tea, sugar, coffee and cocoa, were a particularly heavy burden on working women (The Vote, 27 May 1911).

Nevertheless, there were women for whom even this protest was out of the question. In a letter to the WSPU newspaper Votes for Women (19 December 1913), Mabel Mason, who described herself as a “working woman”, of Wickford, Essex described how she was charged with keeping a dog without a licence. The dog was a stray, ill treated and starving, that she had taken in and looked after.

“In Wickford we are all poor”, she wrote, and “people say, ‘Poor people can’t own they are Suffragettes; it’s too expensive’”. Though she “would dearly have loved to say” she protested against paying for the licence, she thought this would increase the amount of the fine, and she could not afford to pay £2 rather than 11s 6d. (In fact, she was fined 7s 6d, the cost of the licence.) She also pointed out that girls in service could not risk being suffragettes as their employers would not put up with “that sort of thing”. She said she was ashamed that she could not tell the court she was a suffragette, but felt that “Those who can’t help with money can surely do something…If I can do anything to help I shall be so proud”.

Whether or not Mabel Mason was right to think that declaring she refused to pay on principle would increase her fine, she clearly felt she could not take the risk of publicly identifying herself as a suffragette. For some women, being a suffragette was more than they could afford.

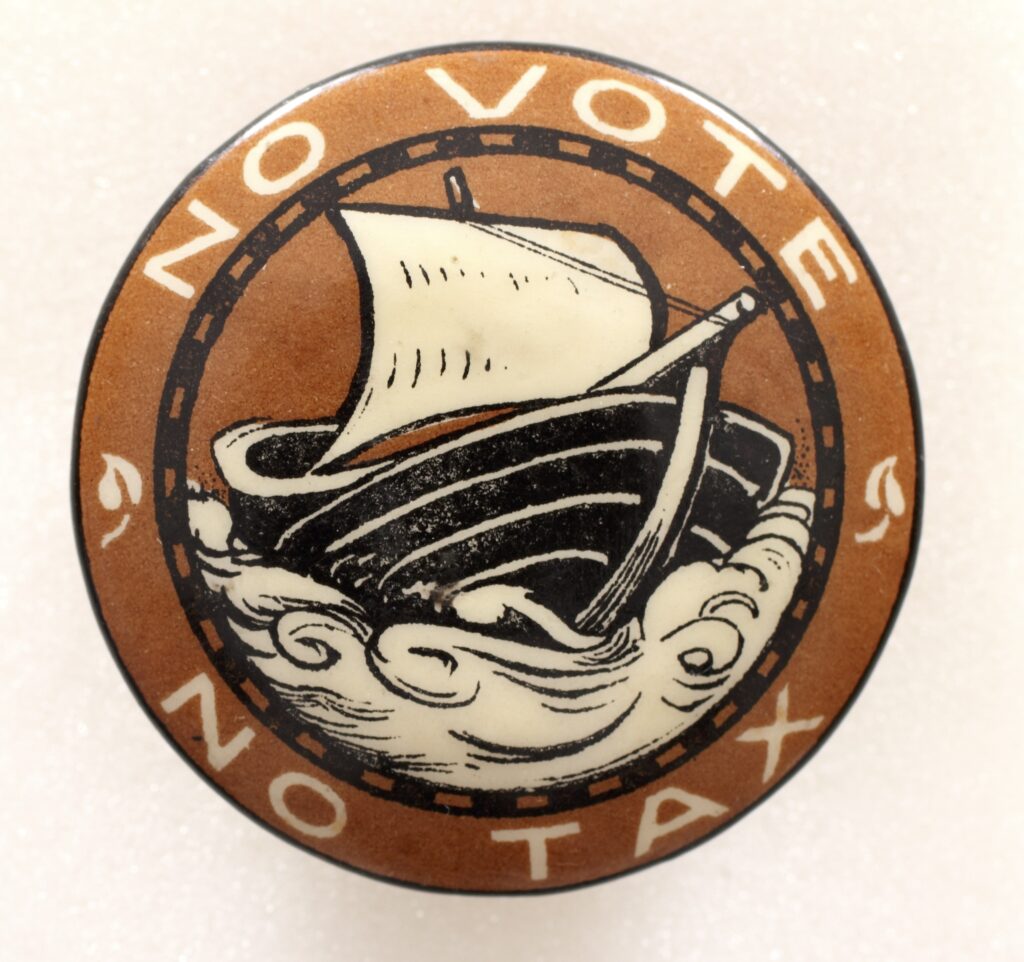

WTRL badge

Picture Credits:-

All images The Women’s Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions