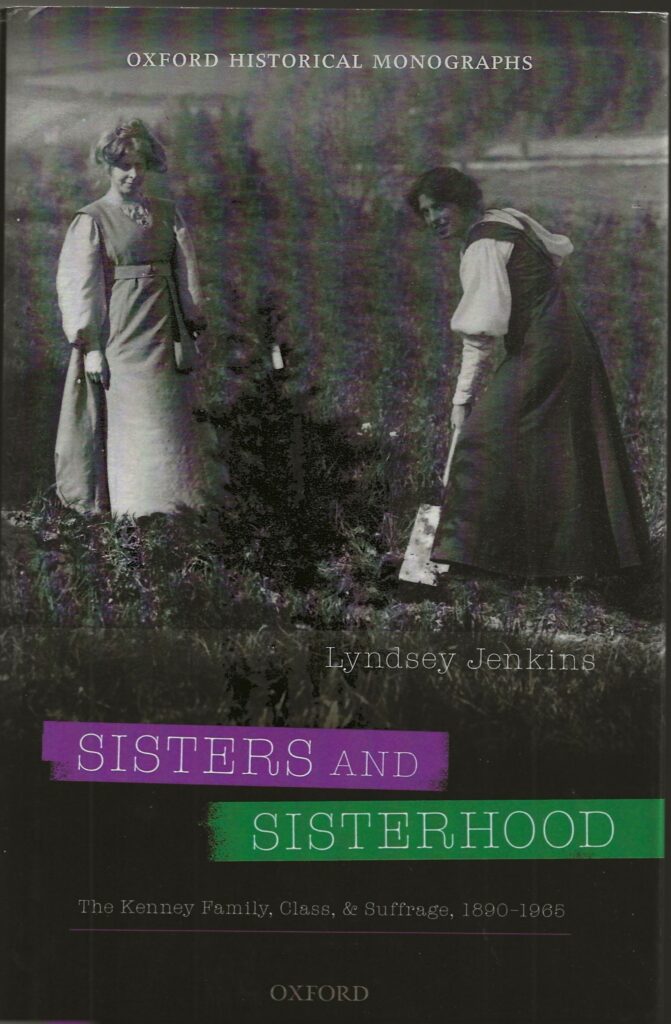

Lyndsey Jenkins, Sisters and Sisterhood: The Kenney Family, Class and Suffrage, 1890-1965 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021)

Posted on 29th March, 2024 in Annie Kenney, Book Review, WSPU

This is a fascinating account of the lives of the Kenney sisters and their involvement in the militant suffrage movement. Annie and Jessie Kenney are probably the best known sisters, but Nell, Jennie and Caroline were also active in the suffrage campaign at various times. Jane and Caroline went on to become Montessori teachers. Mollie and Alice went to live in America, and I’m sure it would be interesting to know more about their lives “outside” the suffrage movement.

The book looks at the lives of the women through a number of perspectives, many of which are rarely considered, and challenge traditional views of Annie, her sisters, and working class women within the militant movement. Much work has already been done to question earlier assumptions that, for example, the movement was London-centric, or all activists were middle class; and to explore the role of men, the anti-suffrage movement, and the context of the campaign.

Jenkins’s aim is to take some of this debate further, “to open up a new conversation around sex, class, and politics, and their interaction in this period”. Of particular interest to me, and perhaps to anyone interested in reading or writing biography, Jenkins also gives a lot of thought to the question of self-representation. Jessie Kenney in particular went to great pains to write and preserve accounts of her experiences and promote her own significance. Like Millicent Price (née Browne), whose biography I am writing, and to whom Jenkins occasionally refers, Jessie wrote an unpublished autobiography, as well as an account of her time in Russia with Mrs Pankhurst in 1917, also unpublished.

There are interesting discussions on the definition of militancy, which Jenkins sees as an identity rather than a set of practices; the importance of the home versus the workplace in the individual’s development; and ideas about maternalism, class and other topics within the movement.

It is interesting to read a book that pays attention to what the suffragettes said as well as what they did, though I couldn’t help wondering if we can always be sure that what someone said in speeches or articles was really their considered opinion, rather than, for example, a reflection of WSPU policy. You see the same arguments repeated in speech after speech and also reproduced in the pages of Votes for Women. Actress and playwright Cicely Hamilton (briefly a member of the WSPU, later of the Women’s Freedom League and the Actresses’ Franchise League) commented on the tedium of “listening to all the old arguments put forth by your fellow-orators” in her autobiography (Life Errant, 1935) and noted that in her own case she “could not always be counted on for an orthodox presentment of the case for enfranchisement.”

The idea that there was an “orthodoxy” may be one that is particular to Hamilton (although according to Jessie Kenney, the delivery of speeches was controlled to the extent that even the speaker’s stance and gestures were directed). Nevertheless, there is a often a sense that a speaker is drawing from a stock of arguments, and manipulating these with a particular end in view. Speeches and articles were delivered for the practical purpose of persuading an audience to accept the WSPU’s point of view, and they were often tailored to suit different audiences.

For example, the sincerity of Annie Kenney’s claim to a German audience that “no nationality, no political creed, no class distinction, no difference of any sort divides us as women” and other utterances on internationalism is hardly borne out by her allegiance to the Pankhursts’ anti-German campaign during the First World War. Jenkins explains their patriotism as an interpretation of internationalism based on the notion that British women held “unique roles within the global struggle”, and discusses the links between the WSPU’s feminism and nationalism. Perhaps, as Poirot would say.

Annie Kenney

One of the reasons I enjoyed this book so much is that it does suggest questions and areas for discussion, making it a stimulating and inspiring read. It offers some interesting new perspectives on the suffrage movement, and by looking beyond the stories of the suffrage years gives a fuller picture of the women’s lives. I’ve often thought too many books and articles give the impression that the suffrage campaigners disappeared in a puff of smoke after the First World War.

Sisters and Sisterhood also confirms the importance of telling more women’s stories. It includes Millicent Price as one of the women whose “unpublished narratives…provide important alternative perspectives which are not always reflected in the better-known accounts”. This is one of the aspects of Millicent Price’s story which drew me to writing about her. So, on a personal level, in Sisters and Sisterhood I have found much to reassure and much that opens up new avenues for my own biographical efforts. I am sure that anyone interested in women’s lives and biography will find much to enjoy too.

Picture Credit:-

Annie Kenney, Women’s Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions.