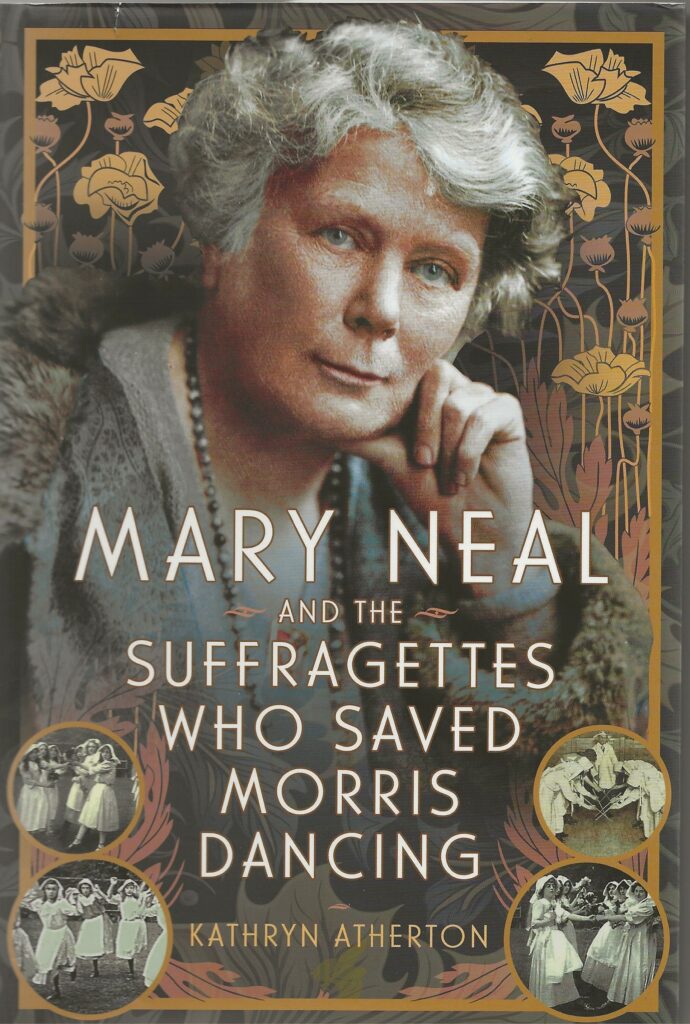

Mary Neal and the Suffragettes Who Saved Morris Dancing, Kathryn Atherton (Pen & Sword, 2024)

Posted on 28th May, 2024 in Biography, Book Review, Mary Neal, Suffragettes

On the face of it, any connection between the suffragette movement and the folk dance revival seems a tenuous one. If all there is to connect them is that some of the women who joined the WSPU were also involved in folk dancing, any link could easily be dismissed as coincidence, and an irrelevant one at that. After all, what correlation can there be between women throwing stones through windows and beribboned girls prancing around in frocks and bonnets with bells around their ankles?

Kathryn Atherton’s biography of Mary Neal is a fascinating exploration of how the two movements were entwined, and perhaps too a reminder that people’s lives are not as compartmentalised as some histories might suggest. Neal was an early WSPU supporter, and also a close friend of WSPU leader, philanthropist and social worker Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, with whom she founded the Esperance Club for working girls. However, as Atherton shows, the links Neal made between the folk dance revival and the suffragette campaign were not only through friendship and group networks. They were also ideological. Indeed, the folk dance revival itself became an arena of conflict in the struggle for women’s equality.

The book gives a clear and sympathetic account of Mary Neal’s upbringing, comparing the comfort of her middle class background, her lack of opportunities, and her yearning for independence to the similar experience of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. Both women’s bids for independence found their outlets in charitable enterprises. Of course, there are problems with this style of philanthropy, with its class, race, cultural and moral attitudes that all too often sought to control the working class as well as improve their lot. However, as Atherton points out, Neal did not remain unaware of the tensions, and later recognised that “charity and philanthropic work were futile”. Neal had realised that they were ineffective against what she called the “hard crust of poverty and degradation in which so many of my fellow creatures lived”.

That being so, how did Neal think something as apparently frivolous as Morris dancing could do anything to tackle “poverty and degradation”? Atherton’s exploration of Neal’s theories are for me the most interesting theme of the book. Neal developed a romantic concept of ‘Merrie England’, the idyllic, pre-industrial and bucolic past which, according to her, Morris dance represented. This linked with “Englishness” and a form of patriotism based on the idea of “uniting a people with its culture as a means of empowerment and liberation”. Neal believed that city-dwelling working girls had an entitlement to inclusion in this culture and a right to a share in the national heritage. She also saw that social reform meant more than the improvement of material circumstances, but also encompassed spiritual, creative and social aspects.

Of course, the problem remains, as with so many histories about the working class, that we only have Mary Neal’s point of view on all this. There’s nothing here about how any of the girls themselves felt or how they perceived the dance; their voices remain unheard. Perhaps they just liked wearing pretty frocks and having a good sing song. And why not? (And on the basis of Atherton’s book, I can’t help thinking Neal would have been all in favour of the girls having fun!)

Left to right: Mary Neal, Emmeline Pethick Lawrence, Lady Constance Lytton

Nor do we hear anything of the “elderly men” who taught Morris dancing to Neal and her dancing girls. Why did they share their skills? What did they think of the way the movement developed? What were their stances on the clash over control of the movement between Neal and Cecil Sharp?

As the WSPU’s campaign progressed, so too did the Esperance Club’s overt connection with it. The girls performed at suffragette fund raisers; Mary Neal wrote for the WSPU newspaper, Votes for Women; and she served on the, albeit fairly moribund, WSPU committee (policy was, in practice, autocratically determined by the Pankhursts). It was partly this connection with a movement he abhorred that led to the rift with Cecil Sharp, with whom she had collaborated in the early days of the folk movement revival. Their dispute extended to argument about which of them deserved the credit for the revival – Sharp described Mary’s claims as impertinent. They also clashed over their approaches to the Morris dance, with Sharp insisting on an academic approach with a fixed and codified style, while Neal took a more evolutionary and interpretive approach. Sharp thought her attitude had given rise to inauthentic embellishments, her girls, for example, “adopting a ‘hoydenish manner of execution’”. Fundamentally, it was a struggle rooted in Mary’s challenge to male expertise.

Mary Neal and the Suffragettes Who Saved Morris Dancing is a fascinating book that reveals some lesser-known aspects of women’s struggle for equality. My only quibbles are the lack of references and the sketchy index. However, these omissions – which probably won’t bother a lot of readers in any case – do not spoil a thoroughly enjoyable and illuminating book.

Picture Credit:-

Mary Neal, Emmeline Pethick Lawrence, Lady Constance Lytton, Women’s Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions