The Human Interest Brothers: Dickens & Character

Posted on 12th October, 2025 in Charles Dickens, Hawkesbury Upton Literary Festival

Even if you don’t read Charles Dickens, you’ve probably heard of some of his characters – Scrooge, for example. But who was his greatest creation? This was the theme of a talk I gave at Hawkesbury Upton Literature Festival’s Tenth Birthday Special on Saturday 27 September 2025. This one day extravaganza of talks, conversations and readings was on ‘Strength of Character’. You can find out more about the festival on the HULF website.

This is quite a long blog, so if you prefer to download it to read, it’s also available as a pdf here.

Even if you don’t like Charles Dickens, don’t like his novels, you have probably heard of some of his characters: Scrooge, Mr Micawber, and Miss Havisham. Perhaps you know something of his villains: the murderous Bill Sikes, the money-grubbing Mr Gradgrind, the sinister lawyer Mr Tulkinghorn. Or some of his heroes: David Copperfield, Oliver Twist, Betsy Trotwood. Or the innocent victims: Little Nell, Nancy, Barnaby Rudge. And then there are all the unforgettable characters in between, what you might call the supporting cast, with their weird, wonderful and very appropriate names: Captain Cuttle, Dismal Jemmy, the Cheeryble brothers, the Artful Dodger, Mr M’Choakumchild, and my personal favourite, Mr Toots.

Captain Cuttle; sketches by James McNeill Whistler

I don’t know how many characters Dickens created; something like one and a half thousand. But many of his characters are problematic. His women are often passive victims, meekly waiting on selfish men: drippy Dora Copperfield; patient Agnes Wickfield looking after her alcoholic father; meek and put upon Amy Dorrit running around after her wastrel father. While it’s true that Dickens’s ideas of feminine goodness are not in line with modern ideas – though I sometimes wonder if in some circles they’re so far out – they do reflect the lives of middle class women as they were lived in his time: hemmed in by restrictions, ill educated, brought up to put their own needs last. I think he shows a great deal of sympathy for them. Some of his portrayals of working women are also very sympathetic, such as Jenny Wren who works her fingers to the bone, also looking after an alcoholic father. And some of his women don’t fit Victorian stereotypes at all: think of David Copperfield’s formidably independent aunt Betsy Trotwood.

Dickens’s most controversial character is, of course, Fagin. The notoriously antisemitic portrayal of the villain in Oliver Twist caused trouble from the moment it was published. The book first came out as a serial in 1860 Dickens’s weekly journal, All The Year Round. A Jewish woman, Mrs Eliza Davis, wrote to him to complain about the prejudicial portrayal of Fagin in the early episodes. Dickens was at first defensive; but in the second half of the book he softened the tone, and in a later edition of Oliver Twist he edited out many of the worst references. Instead of constantly referring to Fagin as “the Jew” he called him by his name or “he”. He also created the noble Jew Mr Riah in Our Mutual Friend, as if to balance out the excesses of his original Fagin.

Nevertheless, the character remains controversial. David Lean’s 1948 film, Oliver Twist, with Alec Guiness as Fagin, caused riots when it was shown in Berlin, and it was not released in America until some years later, after various cuts had been made. Recently the BBC has attempted to portray a more human and balanced character in the children’s series The Dodger, with Christopher Eccleston as Fagin. Eccleston was anxious to get the character right, for example watching Simon Schama’s The Story of the Jews. And author Alison Epstein has just brought out her novel Fagin the Thief, which gives Fagin a first name and a back story.

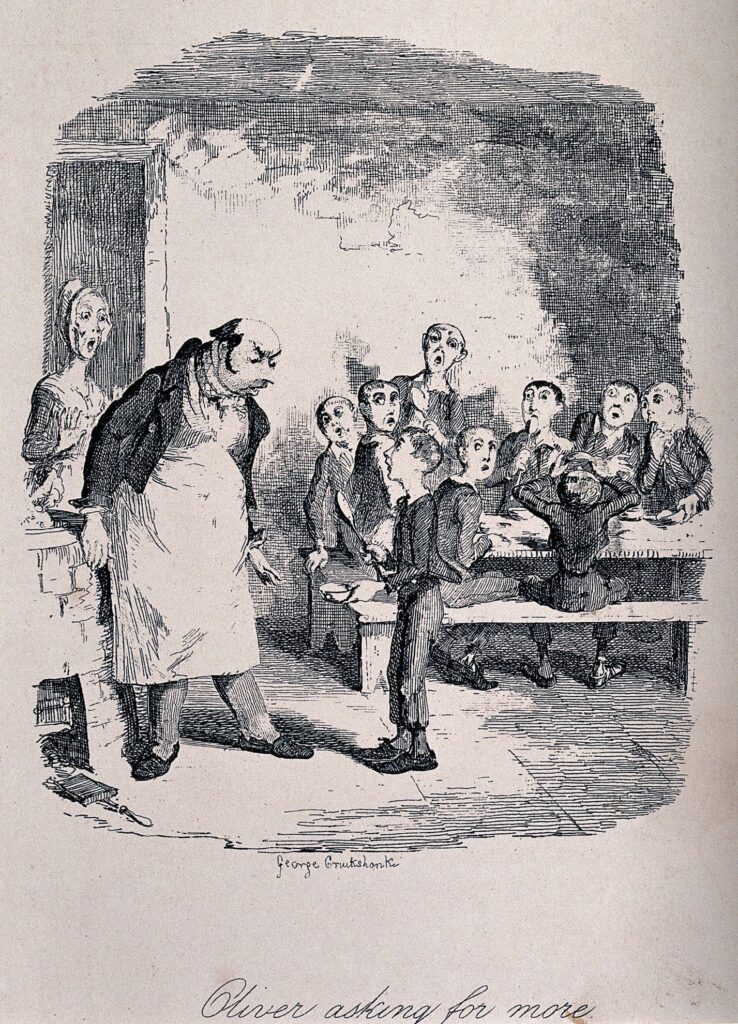

Oliver asks for more.

These characters may be controversial, but there is no denying they are, like all Dickens’s characters, vivid and powerful. But perhaps the best character ever invented by Charles Dickens was – Charles Dickens. And in particular, Charles Dickens as the Uncommercial Traveller.

The Uncommercial Traveller is the narrator of a series of articles or sketches that first appeared in All The Year Round. They were later collected together and published in book form. In these articles, he describes his wanderings around London and further afield. But more than that, he uses them as starting points for social comment, comedy, expressions of his Christian faith, reminiscences, and meditations on mortality.

So who is the Uncommercial Traveller? Here’s an extract from the opening, ‘His General Line of Business’:-

Allow me to introduce myself…I am both a town traveller and a country traveller, and am always on the road. Figuratively speaking, I travel for the great house of Human Interest Brothers, and have rather a large connexion in the fancy goods way. Literally speaking, I am always wandering here and there from my rooms in Covent Garden, London – now about the city streets: now, about the country bye-roads – seeing many little things, and some great things, which, because they interest me, I think may interest others.

These are my brief credentials as the Uncommercial Traveller.

So why do I say that the Uncommercial Traveller is Charles Dickens? Partly because there is so much autobiography in the articles. Charles Dickens himself lived in Covent Garden. Many of the Uncommercial Traveller’s journeys are taken on foot, and Dickens was a great walker. He walked every day, in all weathers, averaging, it is said, twelve miles a day. He was particularly fond of walking at night. In ‘Shy Neighbourhoods’ he describes one of his walks as starting at two am, when he walked thirty miles before stopping for breakfast. He usually walked on his own, using the time to observe, to meditate, and sometimes to dream, sometimes even falling into a trance state. Sometimes he set off with no particular goal in mind. At other times he made up his mind where he was going and stuck to his plan.

Many of the episodes Dickens describes are based on his own experiences. In ‘Travelling Abroad’, the Uncommercial Traveller describes meeting a child on the road between Gravesend and Rochester who dreams of one day owning a house at Gadshill. The Uncommercial Traveller is amazed by this because now “that house happens to be my house”. The boy was, of course, Charles Dickens.

The Uncommercial Traveller also reveals the same concerns that Dickens expressed in his novels, and in his life. There’s his tremendous knowledge of and love for London, and especially its dusty, out of the way corners. He’s particularly fond of walking in the City on a Sunday, when it’s deserted:-

Such strange churchyards hide in the City of London; churchyards sometimes so entirely detached from churches, always so pressed upon by houses; so small, so rank, so silent, so forgotten, except from the few people who ever look down on them from their smoky windows. As I stand peeping in through the iron gates and rails, I can peel the rusty metal off, like bark from an old tree. The illegible tombstones are all lop-sided, the grave-mounds lost their shape in the rains of a hundred years ago…Sometimes there is a rusty pump somewhere near, and, as I look in at the rails and meditate, I hear it working under an unknown hand with a creaking protest: as though the departed in the churchyard urged, “Let us lie here in peace; don’t suck us up and drink us!” (‘The City of the Absent’)

There’s Dickens the romantic, who sees love blossom in the most unlikely places: the bank where a clerk “has over and over again inscribed AMELIA, in ink of various dates, on corners of his pad” (‘The City of the Absent’); in a dentist’s waiting room; in an old people’s home when a one-armed Chelsea pensioner courts an elderly woman. In one of the city churches he visits he witnesses the courtship of two charity children who have been put to work to clean the church – and at the same time he has a sarcastic dig at so-called charity:-

They were making love – tremendous proof of the vigour of that immortal article, for they were in the graceful uniform under which English Charity delights to hide herself …O it was a leaden churchyard, but no doubt a golden ground to those young persons!…They had left the church door open, in their dusting and arranging. Walking in to look at the church, I became aware, by the dim light, of him in the pulpit, of her in the reading desk, of him looking down, of her looking up, exchanging tender discourse…I turned to leave the sacred edifice, when an obese form stood in the portal, puffily demanding Joseph, or in default of Joseph, Celia. Taking this monster by the sleeve, and luring him forth on pretence of showing him whom he sought, I gave time for the emergence of Joseph and Celia, who presently came towards us in the churchyard, bending under dusty matting, a picture of thriving and unconscious industry. It would be superfluous to hint that I have ever since deemed this the proudest passage in my life. (‘The City of the Absent’)

There’s the Dickens who revels in ghost stories and sightings of corpse candles and the spectral dog that presages death, stories of the drowned pulled out of the Thames, tales of horrible crimes, and even more horrible punishments. The Uncommercial Traveller litters his articles, as Dickens litters his novels, with ghoulish images: “the chopped up murdered man”, “hanged men and women”. There are shrouds, and graves, and skulls, and coffins, and vaults full of dead citizens. ‘Some Recollections of Mortality’ includes an account of a visit to the Paris morgue. The Uncommercial Traveller joins the crowd waiting outside to see a body brought in:-

Shut out in the muddy street, we now became quite ravenous to know all about it. Was it river, pistol, knife, love, gambling, robbery, hatred, how many stabs, how many bullets, fresh or decomposed, suicide or murder?…It was but a poor old man, passing along the street under one of the new buildings, on whom a stone had fallen, and who had tumbled dead.

There’s the Dickens who has tremendous contempt for mismanagement, waste, petty bureaucracy, and the official indifference that tolerates suffering and poverty. In 1860, a thousand soldiers in India were discharged from the army and sent home on the Great Tasmania. In one of the Uncommercial Traveller’s angriest articles, ‘The Great Tasmania’s Cargo’, he explained:-

These men had claimed to be discharged, when their right to be discharged was not admitted. They had behaved with unblemished fidelity and bravery…Their demand had been blunderingly resisted by the authorities in India…the bungle had ended in their being sent home discharged…There was an immense waste of money, of course.

The government had not provided enough hammocks for the men, or enough blankets, clothing or food, and what food they had was maggoty and mouldy. Sixty men died on the voyage, and when the ship docked in Liverpool, 140 were taken to the workhouse for medical treatment. When Dickens saw them they were “skeletons”, “racked with dysentery and blackened with scurvy”.

Dickens laid into the officials responsible for the appalling treatment of these men, mocking them as “the Pagoda Department of that great Circumlocution Office, on which the sun never sets, and the light of reason never rises”. The government Circumlocution Office, drowning under paperwork and bureaucracy, devoting itself to making sure that nothing ever gets done, run by nepotism, featured in Little Dorrit.

Dickens ended the article declaring that:-

No punishment that our inefficient laws provide, is worthy of the name when set against the guilt of this transaction. But, if the memory of it die out unavenged, and if it do not result in the inexorable dismissal and disgrace of those who are responsible for it, their escape will be infamous to the Government (no matter of what party) that so neglects its duty, and infamous to the nation that tamely suffers such intolerable wrong to be done in its name.

In the same way, he lambasts official cover ups, political inaction, the empty pomp of the House of Lords and the law courts where judges appear in “goats’ hair and horse hair and powdered chalk and black patches on the top of the head” (‘Medicine Men of Civilisation’), and charity that is not charity and charitable institutions where “the question how prosperous and promising the buildings can be made to look…usually supersedes the lesser question how they can be turned to the best account for the inmates” (‘Titbull’s Alms-Houses’).

He criticised the inadequate provision for the poor, unemployed, sick and elderly. In ‘Wapping Workhouse’ for women he found sick women “in a building most monstrously behind the time – a mere series of garrets or lofts, with every inconvenient and objectionable circumstance in their construction…miserable rooms…wretched rooms”. He found insane women, babies and children, and women picking oakum. He found elderly women, many bedridden, all together in one large ward. In one ward, he found a ninety-three year old widow who had only been in the workhouse for a year, and commented:-

At Boston, in the State of Massachusetts, this poor creature would have been individually addressed, would have been tended in her own room, and would have had her life gently assimilated to a comfortable life out of doors. Would that be much to do in England for a woman who has kept herself out of a workhouse more than ninety rough long years?

And as he left the Wapping workhouse he declared that the wards “ought not to exist; no person of common decency and humanity can see them and doubt it”.

Perhaps nowhere is the Uncommercial Traveller more Charles Dickens than when he writes about cruelty to children. A visit to homes in the East End, which he describes as “A squalid maze of street, courts, and alleys of miserable houses…A wilderness of dirt, rags, and hunger” (‘A Small Star in the East’) shows him dreadful sights enough: a woman suffering from lead poison from the factory where she works; a coal porter with ulcerated legs; families with only one bed between them, nothing to eat, no coal. But worse than anything was the children.

I could not bear the contemplation of the children. Such heart as I had summoned to sustain me against the miseries of the adults, failed me when I looked at the children. I looked at how young they were, how hungry, how serious and still. I thought of them, sick and dying in these lairs. I think of them dead, without anguish; but to think of them, so suffering and so dying, quite unmanned me.”

Perhaps worse still, is the scandal of children living on the streets. He wonders if future generations could imagine “the existence of a polished state of society that bore with the public savagery of neglected children in the streets of its capital city, and was proud of its power by sea and land, and never used its power to seize and save them!” (‘On An Amateur Beat’).

He returns over and over again to the plight of street children.

Within so many yards of this Covent Garden lodging of mine, as within so many yards of Westminster Abbey, Saint Paul’s Cathedral, the Houses of Parliament, the Prisons, the Courts of Justice, all the Institutions that govern the land, I can find – must find, whether I will or no – in the open streets, shameful instances of neglect of children, intolerable toleration of the engenderment of paupers, idlers, thieves, races of wretched and destructive cripples both in body and mind, a misery to themselves, a misery to the community, a disgrace to civilisation, and an outrage on Christianity. (‘The Short-Timers’)

In all these things and more the Uncommercial Traveller speaks with the voice of Charles Dickens.

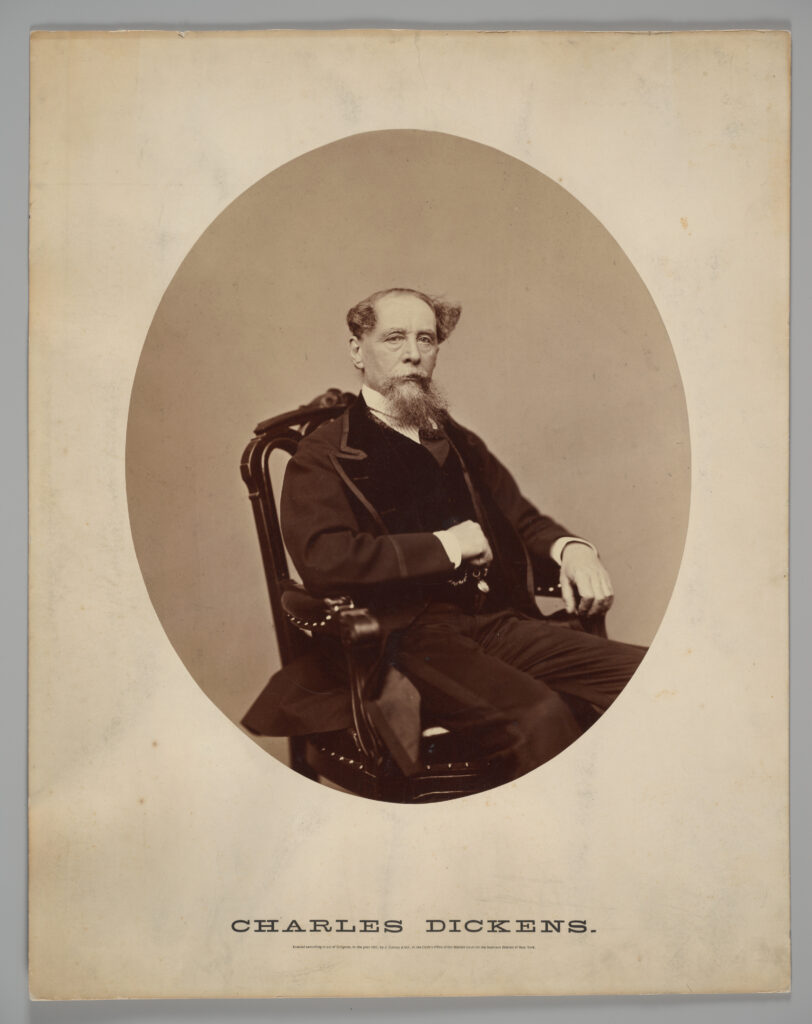

Charles Dickens

Except – does he? Is it true that when a writer creates a narrator, a persona, a voice, she is merely being herself? Can’t they simply be making it up? And isn’t that the way to fall into the trap of thinking that if a writer says something sexist, for example, that writer is themselves sexist? I remember one reviewer of my novel To The Fair Land accused me of sexism because one of my eighteenth-century characters expressed the view, common at the time, that women couldn’t write good books. As if that wasn’t enough, someone else pitched in with “huh! If it’s sexist I’m not going to read it then”.

Still, I think there’s as at least as much Dickens in the Uncommercial Traveller as there is in his novels, speeches and letters. But there is more than that. Dickens tells us that he has not become an Uncommercial Traveller as an adult: he’s been an Uncommercial Traveller all his life, from his childhood days when he was “Master Uncommercial”, and from the days, twenty five years ago, when “I was a modest young commercial…timid and inexperienced” (‘Some Recollections of Mortality’). The Uncommercial Traveller isn’t a character jumping fully created and complete from the page.

The introduction to the Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Uncommercial Traveller notes that in 1859 Dickens gave a speech to the Society of Commercial Travellers’ Schools, which was a charity for children or orphans of travelling salesmen. In his speech he said,

We should remember tonight that we are all Travellers, and that every round we take converges nearer and nearer to our home; that all our little journeyings bring us together to one certain end; and that the good that we do, and the virtues that we show, and particularly the children that we rear, survive us through the long and unknown perspective of time.

Who is the Uncommercial Traveller?

We are all Uncommercial Travellers.

The Uncommercial Traveller, Charles Dickens (OUP, Oxford World’s Classics, 2021, ed Daniel Tyler)

Picture credits:-

Captain Cuttle (a Character from Charles Dickens’s Dombey and Son) (from Sketchbook); James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Margaret C Buell, Helen L King, and Sybil A Walk, 1970, Public Domain

Oliver Twist, holding a bowl and a spoon, asks for more food, while other children and a woman look surprised. Etching by George Cruikshank, Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

Charles Dickens, 1867, J Gurney & Son (Active 1860–1874), Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005, Public Domain