The Lady Secretary

Posted on 9th February, 2026 in Office Work, Secretary

I’ve written before about my interest in the history of women office workers, and how women came to dominate secretarial and clerical jobs. (See ‘Being A Secretary’ .)

As part of the research for the novel I’m currently writing (Death Goes to Plan: A Garden City Mystery), I’ve been looking into secretarial work during the 1900s in more detail. I’ve found an incredibly useful source in a book edited by Herbert E Blain, Pitman’s Secretary’s Handbook: A Practical Guide to the Work and Duties in Connection with the position of Secretary to a Joint-Stock Company, Public Institution, Member of Parliament, etc. I have a copy of the 1908 edition, published by Pitman & Sons, which contains fascinating chapters on such topics as opening letters, margins, loose leaf ledgers, newspaper cuttings, and much more.

One thing that’s very obvious about the book is the assumption that secretarial work was a career for men. “Parents confronted with the necessity of selecting an occupation for their sons…”, “middle-class boys”, “Shorthand Increases a Man’s Ability and his Capacity for Work” and so on and so on. Women don’t get a mention.

Interestingly, by the time the 1935 edition of The Secretary’s Handbook came out, that had changed. Blain notes that “the entry of the gentler sex into the business world has been largely noticeable for the success attained by Lady Secretaries, with their expert knowledge of shorthand and typewriting, and this work appears specially suitable for those of good education.” The Lady Secretary was, Blain explains, one “of the higher grades” of secretarial work. To mark their entrance into the business world, the 1935 edition has a new chapter entitled ‘The Lady Secretary’. What a brilliant chapter it is!

In it, Blain outlines the qualities required by a Lady Secretary. They include education, industry, patience and perseverance, self-respect, self-control and self-devotion – the last three relate to avoiding an employer’s unwelcome advances (known today as sexual harassment). She should have a good command of English – and after all, it is the “weaker sex” which makes the most spelling mistakes. Too many women, Blain reminds us, don’t put proper addresses or dates on their letters, they don’t use proper punctuation, and they put the chief point of the letter in the postscript, or leave it out completely. The Lady Secretary will, of course, know better. And, of course, she should learn the “twin arts” of typewriting and shorthand, where women’s “flexibility of finger and rapidity and lightness of manual execution stand them in good stead”.

She must regard her employer as “perfect”, although he won’t be of course – but then, neither is she. Still, it’s wise for her to “cultivate the belief” that he is perfect. She should drop the notion of a “tall Adonis, who will always be the pink of respectful courtesy, who will never be impatient and never cross, who will always arrange his work that the Secretary may leave promptly to time…” She should drop, too, the dream of “little vases of violets upon typewriter desks, as a preliminary…to leading the ‘typine’ to the altar”. Nevertheless, she should study her “chief’s” moods and idiosyncrasies “even more thoroughly than would a wife”.

The Lady Secretary may not find a husband (except in the imaginings of “the lady short-story writer”) but she will have to avoid “temptations and dangers” that could lead to the loss of character. There are employers who will “attempt…to become on terms of undue familiarity” with his secretary. She should know how to set boundaries, and take the trouble to find out from other employees “particulars as to her predecessors or as to the reputation of her ‘Chief’, for no man is a hero to his office boy”. If her employer takes liberties, she should resign immediately.

Blain follows up with a chapter which includes accounts of their work by a number of women. These are, he says, “the actual words used by Lady Secretaries”. What stands out from the women’s accounts is the variety of duties the job might entail: managing finances, arranging meetings, diary management, taking dictation and also composing letters, and dealing with enquiries. There were all sorts of odd jobs specific to their employment, such as writing menus in French, or, in the case of a school secretary, occasionally travelling with the pupils. As one woman noted “Indeed, one must ‘fit in’ where one is put”. Their experiences show how flexible they had to be about their working hours. Working late or at times to suit their employers were part of the job.

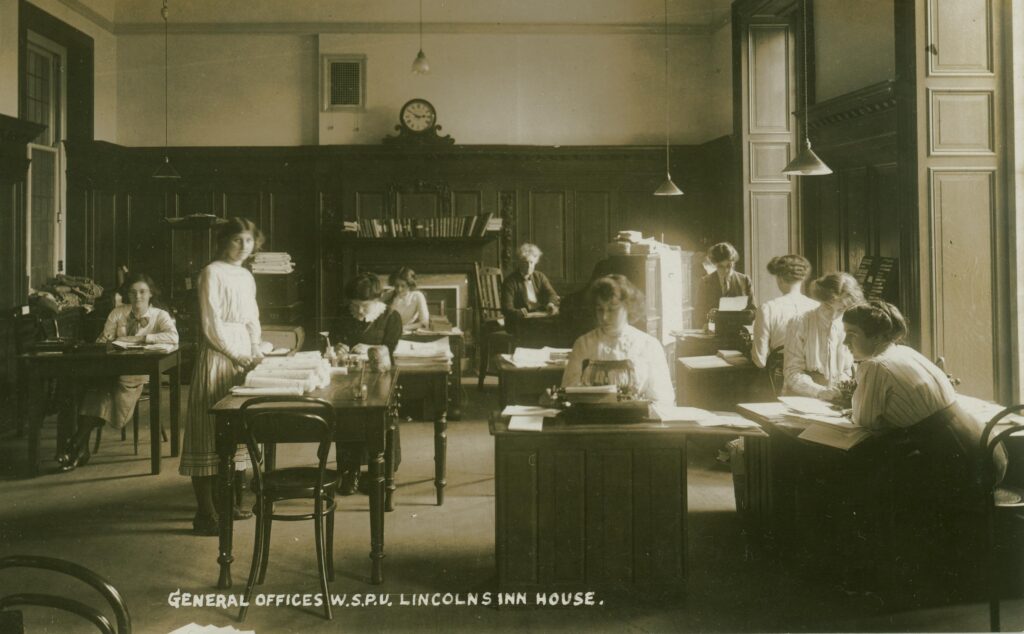

Offices of the Women’s Social & Political Union, Lincoln’s Inn House, London 1913

A Secretary to a Private Gentleman explained that hers was a residential post, which meant that correspondence was not given to her until 9 pm. She typed it up the same evening or left it to morning, “according to circumstances”.

A Secretary to a Private Lady “who is engaged in a good deal of public and private enterprise of a varied nature” worked in a “luxurious and dainty apartment” in her employer’s house. Her work involved helping with the management of the estate, running the village library founded by her employer, and keeping details of pensioners and records of their entitlement to coal and meat. Her hours were irregular: “I never quite knew when I might be called upon to do some work”. Christmas was a particularly busy time, and she recalled one occasion when she was given typing at 5.30 which had to be ready by 7.30, during which time she also had to fit in “flying upstairs…to do a lightning change into evening dress, I managed it just as the gong was sounding!” On the other hand, when her work was done “my time was my own, and I was able to join in the motoring, driving, or walking, with other members of the household”.

A Secretary to a Mission Organiser worked from 9.30 to 5.30, with an hour and a half for lunch, but she never left the office before 6pm. She often had to work later than that or go back to work in the evenings. She organised meetings and took minutes, as well as answering enquiries, paying accounts, and managing office supplies. “A secretaryship,” she wrote, “is no sinecure!”

A Secretary to a Church Official worked for committees involved in missionary work. She had the mammoth task of arranging meetings for up to eighty people, issuing notices, preparing and circulating minutes and agenda. She enjoyed the work: meeting the members “who hail from different parts of the district” gave her “a peep into human nature”. The office was old-fashioned, but they did have typewriters. Her knowledge of French was useful, and she was learning shorthand.

A Lady Secretary to a Member of Parliament took most of her dictation in “phonography”, by which she means shorthand. However, less than half of her time was spent on typing and shorthand. She had charge of petty cash, and answered “telephonic” and other enquires. And, she adds, “Perhaps the most difficult thing of all, make excuses for a man who usually fails to keep appointments to time and know a little about the callers’ business, so as to be able to entertain them while they wait”.

It’s a fascinating glimpse into the work and lives of these women. For many women, Blain points out, office work offered “useful, congenial, and oftentimes very remunerative work”. However, it was at the cost of long hours and putting her employer’s interests firmly before her own.

Picture Credit:-

Offices of the Women’s Social & Political Union, Lincoln’s Inn House, London 1913, Women’s Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions